by Dave Hampton

Whose density? Informal settlements ring the hillsides of Port-au-Prince. Source: IOM/UN-Habitat.

In my previous post, I addressed some assumptions author Vishaan Chakrabarti makes in How Density Makes Us Safer During Natural Disasters.

I don’t mean to single out Mr. Chakrabarti – many of his points are well-taken. Among them the reduced energy consumption of urban dwellers, balanced by his acknowledgment that “[r]egardless of the inherent environmental advantages of urban living, however, cities are vulnerable sets of materials and systems, and Sandy revealed some of their glaring deficiencies.” We at messysystems.com can certainly appreciate the notion of a city’s resilience as a resultant of its systems.

However, let’s look at examples of when density does and doesn’t make ‘us’ safer during disasters, especially on this, the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Sandy’s landfall on the East coast of the United States.

A debris-choked street in the dense Port-au-Prince neighborhood of Delmas 32, May 2011. Photo by the author.

Which disaster?

During (and after) which disasters is density an asset, and where?

Port-au-Prince, for example, fared poorly during (and after) the 7.0 magnitude earthquake which struck the island nation of Haiti on January 12, 2010. While the epicenter was 16 miles (25 km) distant in Léogâne, the capital city, with a population density on par with Mumbai or Kolkata, still experienced widespread injury, death, population displacement, and devastation to buildings and already overtaxed and inadequate infrastructures. Recovery efforts were hampered for years by millions of tons of debris lining very narrow streets, such as those in the highly-dense neighborhoods of Delmas. 250,000 buildings, many already inadequate in terms of life safety, were left in varying states of damage, often remaining occupied. Demolitions of unsound buildings still occur today, and, though progress has been made, displaced Haitians still number in the hundreds of thousands, nearly 4 years after the quake.

Suffice to say, density in terms of population or disposition of dwelling units was not an asset for Port-au-Prince, either during or after its recovery from disaster. But, is it unfair to compare the resilience of the capital city of the poorest nation in the Western hemisphere to New York City? Possibly.

Let’s try this:

Marcial Blondet, an engineering professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru who helped develop earthquake-resistant reinforced adobe homes, compares three recent earthquakes of powerful magnitudes: Pisco, Peru in 2007 (mag. 8.0); Chile in 2010 (mag. 8.8); and Haiti in 2010 (mag. 7.0). While Pisco is considerably less dense and urban than, say, Santiago, Chile and far less than Port-au-Prince, the loss of life comparisons are startling: 519 in Peru, 521 in Chile, and somewhere between 49,190-316,000 in Haiti.

The point being: Chile, a country with a GDP per capita income over twice that of Peru and nearly 20 times that of Haiti, yet over three times less than the U.S., was prepared for the type of disaster that befell it. After experiencing a devastating earthquake in 1960, building codes and inspection, good design, engineering and construction, and high emergency response capability were prioritized.

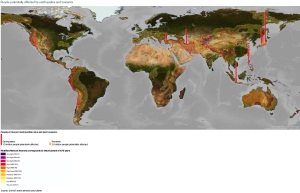

People potentially affected by earthquakes and tsunamis. Source: Swiss Re. See below for the full report.

Who is ‘us’?

Second, we need to define the ‘us’ in ‘density makes us safer’: where are people and assets most at risk?

In Mind the risk: A global ranking of cities under threat from natural disasters, Swiss Re, a company which knows a thing or two about urban risk and resilience, identifies 616 urban areas and their loss potential from a range of disasters: earthquakes, storms, storm surges, tsunamis, and river flooding. The indicators are the size of the urban population and impact on the local and national economy. The metropolitan areas most at risk from multiple types of disasters: China’s Pearl River Delta, and Japan’s Osaka-Kobe and Tokyo-Yokohama regions, all highly densely populated regions.

The study acknowledges the preponderance of those high-production, high-income areas as being the most risk-averse since the evaluation criteria focuses on standardized absolute values of working days lost. Thus, Tokyo-Yokohama tops Jakarta, though population numbers are comparable between the two. However, when productivity losses of a city are weighed in relation to the GDP of an entire country, “a smaller country with only one or a handful of urban centres can end up in the first ranks because these cities play an essential role to their home country’s national economy. …These local rankings give an indication of how a disaster can impact the resilience of a whole nation.”

While New York City’s influence on its state, region, and the nation is uncontestable, its overall loss potential is lower, in context, due in part to the types of disasters which it is most likely to face.

Thus, the who and the where of dense urban areas holds great weight in determining resilience to disasters.

An urban system, just messy enough: a canal (left) doubles as a market corridor (right) in Ravine Pintade, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Photo by the author.

Systems matter

Again, as Mr. Chakrabarti acknowledges “…cities are vulnerable sets of materials and systems.”

An economic powerhouse metropolis in a developed nation, New York has everything going for it. Density, admittedly, concentrates people, power, and capacity.Years of focused prioritization – with little chance this will evaporate anytime soon, regardless of the impending end of Bloomberg’s reign – have produced a highly sophisticated set of checks and balances in the form of strong building and health codes, zoning laws, inspections enforcement, and robust support networks of emergency response and public health.

Where Port-au-Prince struggled during the immediate aftermath of the 2010 earthquake, and continues to do so in the recovery period in part because of numerous pre-quake shortcomings, New York City’s many systems, despite some fits and starts during and after Hurricane Sandy, will ultimately prove more resilient.

Over the coming months, we look forward to exploring how these kinds of systems work, and the lessons which can be shared to make many places the world over more resilient. We hope you’ll join… and contribute.